Gastroshiza in Newborns: Causes, Pathophysiology & Treatment

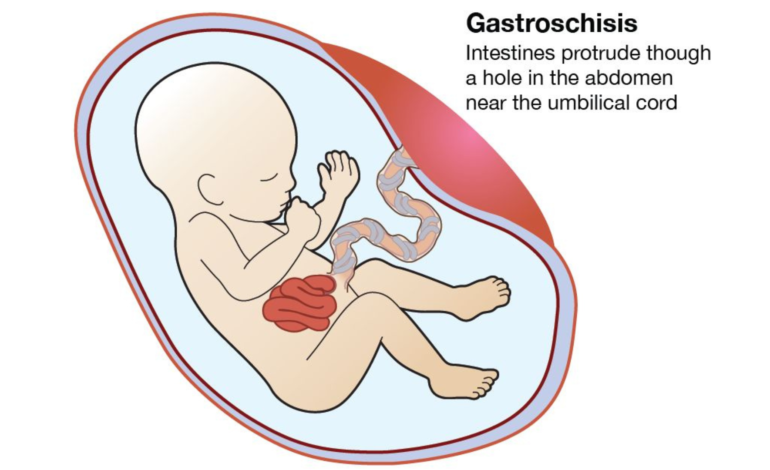

Gastroshiza is a rare but severe congenital disability affecting a baby’s abdominal wall. It occurs when an opening forms next to the belly button. This opening allows the intestines—and sometimes other organs—to push outside the body. Unlike other abdominal wall defects, the exposed organs in gastrochisis lack a protective membrane. This makes early diagnosis and prompt medical care essential.

Typically, gastrochisis is detected during pregnancy and needs specialized surgery soon after birth. Thanks to modern medicine, survival rates have greatly improved, though long-term care may still be needed.

What Is Gastroshiza?

Gastroshiza is a congenital disability that develops early in pregnancy, usually in the first trimester. It appears as a hole in the abdominal wall, often to the right of the umbilical cord. The baby’s intestines extend outside the body and are directly exposed to amniotic fluid.

Without a protective sac, prolonged exposure can irritate and damage the intestines, complicating post-birth treatment.

Causes of Gastrochisis

The precise cause of Gastroshiza remains unclear. However, researchers think it results from abnormal abdominal wall development early in fetal growth. Several risk factors are linked to a higher likelihood of this condition.

One strong risk factor is young maternal age, especially during teenage pregnancies. Maternal smoking, alcohol use, and recreational drug exposure during pregnancy also raise the risk. Certain medications taken early in pregnancy might contribute as well. Nutritional deficiencies, remarkably low folic acid levels, are another suspected factor.

Gastrochisis is not typically inherited and does not usually run in families.

Symptoms and Physical Signs

Gastroshiza is noticeable at birth. The most prominent sign is the intestines outside the baby’s body through an opening near the navel. Sometimes, the stomach or other organs may also protrude.

Newborns may show signs of intestinal swelling, thickening, or discoloration due to exposure to amniotic fluid. Feeding difficulties, abdominal inflammation, and dehydration are common until surgical repair.

During pregnancy, mothers usually experience no physical symptoms, making prenatal screening vital.

Diagnosis During Pregnancy

Gastroshiza is often diagnosed through a routine prenatal ultrasound, usually in the second trimester. Ultrasound imaging reveals free-floating bowel loops outside the fetal abdomen. Elevated maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels may also indicate an abdominal wall defect.

Once diagnosed, the pregnancy is closely monitored to assess fetal growth, bowel condition, and overall health. Delivery typically occurs at a hospital with neonatal intensive care and pediatric surgery facilities.

Treatment and Surgical Management

Treatment for gastrochisis starts immediately after birth. The exposed organs are protected to prevent infection and dehydration. The baby is stabilized before surgery.

Surgical repair can be done in two ways. In mild cases, a single surgery places the organs back into the abdomen and closes the opening. In severe cases, a staged approach is used, gradually returning the intestines into the abdominal cavity over several days with a sterile pouch, followed by final closure.

After surgery, the baby is monitored in the neonatal intensive care unit. Feeding is introduced slowly, often starting with intravenous nutrition until the intestines function normally.

Possible Complications

While survival rates are high, Gastroshiza can lead to complications. These may include intestinal blockages, poor nutrient absorption, infections, or prolonged feeding intolerance. Some babies may develop short bowel syndrome if part of the intestine is damaged and needs removal.

Extended hospital stays are common, but many children fully recover with appropriate care.

Long-Term Outlook and Prognosis

The long-term outlook for babies with gastrochisis has dramatically improved. Most children grow up healthy and develop normally. Some may face digestive issues early on, but these generally improve over time.

Regular follow-ups with pediatric specialists help ensure proper growth, nutrition, and intestinal function.

Prevention and Risk Reduction

Since the exact cause of Gastroshiza is unknown, there’s no guaranteed way to prevent it. However, reducing known risk factors can help. Staying away from smoking, alcohol, and drugs during pregnancy is very important for the health of both the mother and the baby. Good prenatal care, balanced nutrition, and adequate folic acid intake are highly recommended.

Early prenatal screening allows for timely planning and better outcomes.

Pathophysiology of Gastrochisis

Embryological Defect

Gastroshiza arises from abnormal development of the abdominal wall during early pregnancy, usually between the fourth and eighth weeks. Typically, lateral body folds move toward the midline and fuse to form a complete abdominal wall. In gastrochisis, this fusion fails, creating a full-thickness defect, often to the right of the umbilical cord. This failure allows abdominal organs, mainly the intestines, to herniate outside the fetal abdomen.

Vascular Disruption

A significant theory about gastroshiza involves vascular issues during embryonic development. Disruption or abnormal regression of the right umbilical vein or omphalomesenteric artery can lead to localized ischemia and tissue damage. This vascular insult weakens the developing abdominal wall, preventing proper closure and creating the defect.

Amniotic Fluid Exposure

Once the intestines herniate, they are exposed to amniotic fluid throughout gestation. This fluid contains digestive enzymes, bile salts, and inflammatory substances that irritate the bowel surface. This exposure can cause inflammation, swelling, thickening, fibrosis, and shortening of the intestinal loops.

Intestinal Dysfunction

Chronic inflammation disrupts normal intestinal function. After birth, affected infants often face feeding intolerance, delayed bowel function, and reliance on parenteral nutrition. In severe cases, reduced blood supply can lead to intestinal atresia, necrosis, or perforation, increasing surgical complexity.

Abdominal Compartment Considerations

Prolonged exposure of the intestines can lead to an underdeveloped abdominal cavity. When the bowel is returned during surgery, increased abdominal pressure may impair breathing and blood flow, often requiring staged surgical closure.

Final Thoughts

Gastroshiza is a severe congenital condition. However, with early diagnosis, expert surgical care, and modern neonatal support, most babies have positive outcomes. Awareness, prenatal monitoring, and advancements in pediatric surgery continue to enhance survival rates and quality of life for affected children.